Five years of agroforestry in Togo and Burkina Faso

We've been investing in dynamic agroforestry in Burkina Faso and Togo since 2021. Our goal is to increase sustainability and boost income for family farmers. Let's take a moment to see how far we've come.

"The neighbours laughed at me and asked me what I was cooking up." These are the words of one of the first courageous Togolese farmers who joined our dynamic agroforestry experiment. "Initially, the farmers and even gebana's agricultural technicians were extremely sceptical," says Michael Blaser, Head of Projects at gebana.

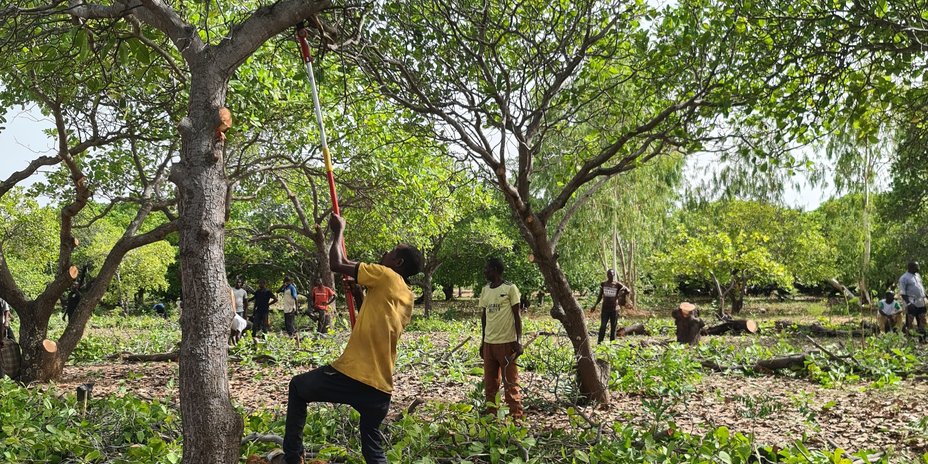

The farmers' reservations are understandable. Dynamic agroforestry requires them to make significant changes to their plots and, in some cases, even cut down trees. But it takes months or even years before they see any results. This is why many farmers initially felt that their livelihood was being threatened.

In both Burkina Faso and Togo, our employees convinced some of the bolder and more innovative farmers to use part of their land to establish demonstration plots. As these plots began to yield results – more resilient plants and additional crops – scepticism slowly turned to interest. "When we looked at our grandparents' cocoa trees during the dry season, we saw that the entire field was devastated and only three or four plants were left. Then, gebana's field agents explained their method to us. We found it interesting and adopted the system," says Patrice Edoh, a cocoa farmer in Togo.

Field agent Eyram Kpomedzi (right) and Patrice Edoh on his plot with dynamic agroforestry

There is still much to do

Today, 595 plots in Burkina Faso are cultivated using dynamic agroforestry methods. At an average of 0.25 hectares per plot, this corresponds to a total area of around 150 hectares – that's 0.4 per cent of the land used to grow our cashews and mangos. In Togo, 164 plots have been converted to dynamic agroforestry so far. That corresponds to 41 hectares, or 2.1 per cent of the land used to grow our cocoa.

This means there is still much to do. The transition to agroforestry is complex and takes a lot of time, so it's still going to be a while before we can report more impressive figures.

The impact of our efforts to date is nevertheless remarkable. Since the project began in Burkina Faso, the average yield on converted plots has been 29 per cent higher than on comparable plots that are farmed organically. But it's not just the yield of the main crops that has increased. In Togo, for example, family farmers harvested around 50'000 kilograms of various crops from their cocoa plots between 2021 and July 2025. These included cassava, bananas, corn and beans, and even papaya and spices. The additional crops have a positive impact on the diets of the family farmers. They can also bring in extra income if the farmers sell them at the local market. By diversifying their plots, producers become more resilient to crop failures affecting individual crops. "We now have a wide variety of plants. And it only takes two to three months for them to produce a yield. I can already harvest the plantains whenever I need them and sell them so that the children can go to school," says Edoh. A combination of plant species has been carefully selected to allow the soil, which had been depleted by monoculture, to recover.

New approaches needed to tackle high costs

Dynamic agroforestry remains expensive – both for gebana and the family farmers. It costs us around CHF 350 to convert a 0.25-hectare plot in Burkina Faso. This includes the cost of equipment, training, seedlings, seeds and their supply. And in recent years, droughts have made growing seedlings even harder and more expensive. In the tropical rainforests of Togo, where we source our cocoa, everything grows really fast. But this also means the young trees need regular maintenance, like weeding and pruning. "This is very physically demanding for many of the older producers, but hiring additional workers would increase the costs," explains Chiaratou Oceni, project coordinator and gebana Togo.

Thanks to our experience in the region, we have now managed to establish our own nurseries and are less dependent on external suppliers. In 2025, we raised a total of 40'600 seedlings in Burkina Faso, 34'600 of which were grown in a nursery run by gebana and 6'000 in five other nurseries belonging to cooperatives. There are currently 25 nurseries operating in Togo. These nurseries have grown a total of 335'459 cocoa tree seedlings and other seedlings over the past five years.

We're continuing to work on reducing costs even further, as Chiaratou Oceni explains: "For one thing, we now use fewer varieties of plants (14 instead of 29). And family farmers are providing their own seeds. As a result, it now costs 43 per cent less to set up a plot in Togo than it did at the start of the project." On plots that still produce a good yield, family farmers leave the cocoa trees in place and try to rejuvenate them through proper pruning. Many producers prefer this approach as it offers the benefits of dynamic agroforestry at a lower cost and with less risk.

"gebana is in charge of the agroforestry activities at the moment. Four of us come to the plot to help the farmers tend to it," says Eyram Kpomedzi, field agent at gebana Togo. "The idea is that they will eventually be able to manage it themselves. But if a producer wants to do more on their own at this stage, they are free to do so." For example, pioneer Edoh has planted papayas on another one of his plots . The trees are already two metres tall and bearing fruit. He plans to plant more plantains soon.

In both countries, project funds from our wholesale customers, such as Esselunga or Coop – through the Coop Sustainability Fund and Halba – as well as government development organisations such as the German Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), are helping to finance the transition to dynamic agroforestry. Given the costs involved, we won't be able to manage without external financing in the long term. But it's worth the effort: in Togo as well as Burkina Faso, the results so far have been positive – both for family farmers and the environment.

Login

Login